Suche

Lesesoftware

Info / Kontakt

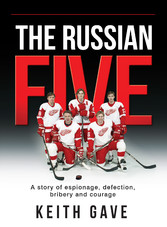

The Russian Five - A Story of Espionage, Defection, Bribery and Courage

von: Keith Gave

Gold Star Publishing, 2018

ISBN: 9781947165441 , 200 Seiten

Format: ePUB

Kopierschutz: DRM

Preis: 11,89 EUR

eBook anfordern

CHAPTER 1

A Special Assignment

A month or so after the annual National Hockey League entry draft, in mid-July 1989, a time when most folks involved in the league were enjoying some respite between seasons, my phone rang. Jim Lites was on the line inviting me to lunch. Strange timing, I thought, to hear from the executive vice president of the Detroit Red Wings, then the son-in-law of owners Mike and Marian Ilitch. I had a good working relationship with Lites, but I usually only heard from him like this after I’d written something he didn’t like. He’d rant, I’d listen, we’d agree to disagree, and it was over. But I hadn’t written anything in nearly two weeks. I was on vacation. I figured Lites wouldn’t be asking to meet if it wasn’t something important.

The next day, we were sitting across from one another at the recently renovated Elwood Bar and Grill, which at the time was across Woodward Avenue from the Fox Theatre. The Ilitches bought and, with Lites running the project, refurbished the Fox and turned it into a showpiece that would ignite the renaissance of Detroit’s embattled downtown. We ordered soup and sandwiches. Lites began to speak.

“Just let me say right up front that if I cross any lines here or make you uncomfortable in any way, I’ll stop and that will be the end of it,” he said.

I raised my eyebrows. After a pause, Lites continued. A lawyer in his mid-30s with a quick smile beneath a prematurely receding hairline, he tended to speak quickly, but always choosing his words carefully. While doing little to conceal his emotions, Lites was always in control of the conversation. He laughed easily, and when he did the whole room laughed with him. When he was angry, and I saw that side of him frequently enough, you knew it before he said a word. Now, he was serious – as though he was about to deliver some distressing news. And he got right to the heart of his subject as our sandwiches arrived.

“We’re prepared to pay considerably – serious money,” he said. “We can assure you exclusivity to any stories, book rights, you name it.”

“Hold on,” I said, using my hands to signal a time-out. “What are you talking about?”

“As you know, we drafted a couple of Soviet players in the draft a few weeks ago.”

I nodded. Of course I knew. I had written about it at length in the pages of the Detroit Free Press. It had been a historic moment for a global sport when the 21 National Hockey League clubs gathered for their annual entry draft, taking turns selecting amateur players from junior hockey, colleges and universities, and European leagues. The Red Wings had chosen center Sergei Fedorov in the fourth of 12 rounds – the highest a Soviet-born player had ever been claimed. In the 11th round, they selected defenseman Vladimir Konstantinov.

“We’ve learned that the Russians are holding part of their training camp in Finland in August, the Soviet National Team,” Lites said. “They’re playing an exhibition game against one of the Finnish elite teams in Helsinki.”

“And?”

“And you’re the only person I know who speaks Russian.”

I sat back in my chair. Stunned silent, I listened to his pitch. Lites explained that he and the ownership family were hoping I could use my cover as a sportswriter credentialed by the National Hockey League to attend that game in Finland. While there, I could “interview” Fedorov and Konstantinov, and perhaps covertly pass along the message that the Red Wings were interested in bringing them to Detroit as soon as possible, even if that meant an unlawful departure from a country that had no intention of allowing them to leave.

“We want you to contact Fedorov,” Lites explained. “Konstantinov, too, though we think he’ll be a lot harder for us to get out because he’s married and has a child. “You could write a letter…”

That letter would provide some background about Detroit and the Red Wings. I could outline some important financial terms and provide contact information to help them begin the process, Lites said. When they were ready, the Wings would use all their power, political influence and money to bring them to North America – the sooner the better.

“You know hockey, you know the league, and you know us,” Lites said. “And as a member of the media, you can get access to those guys when nobody else in the NHL can. All we’re asking for is that you make that first contact for us. We can take it from there – if it’s going to happen – but we can’t do anything without that initial contact.”

Though I tried not to show it, I was both excited and conflicted, flattered and at the same time offended. My heart was telling me one thing, that this could be the story with the potential to define my career. My head, however, screamed that I should be insulted that Lites would even broach a subject like this. But I was also more than a little intrigued. In six years in the intelligence business as a Russian linguist working for the National Security Agency, I never got close to such a mission. Here was, in every respect, a magnificent opportunity for an actual cloak-and-dagger assignment.

“Impossible,” I said abruptly. “I can’t do it. No way. Not a chance.”

“Enough said then.” Lites allowed the subject to drop after apologizing, insisting he hadn’t meant to offend me.

We made small talk, finished our lunch and parted. I felt lousy

A few weeks later I was on board a Northwest Airlines/KLM flight to Boston and then on to Helsinki, by way of Copenhagen, Denmark, with an important message for a couple of prominent young Soviet hockey players.

Since that meeting with Lites, my days were restless and my nights sleepless as I wrestled with the notion of accepting his offer. I had explained my dilemma, that it would be ethical suicide to enter into some sort of financial arrangement to do such a favor for the team I was assigned to cover. My allegiance was totally and completely to the newspaper that entrusted me with the challenge of a professional sports beat and paid me well to cover the Detroit Red Wings as thoroughly and as fairly as I could. And especially to its readers, who included some of the most passionate and knowledgeable hockey fans in the world.

This could cost me my job. But while I worried about putting my career in jeopardy, I also argued with myself, trying to justify my heart’s position, that I would be doing my newspaper a great disservice if I didn’t leverage as much of an advantage as possible over the competition in a city that prided itself in having two great daily newspapers. Besides, Cold War history cannot be written without stories of correspondents for the great Western news organizations occasionally used as pawns to send messages between covert agents representing the Soviet Union and the United States.

Indeed, entire books have been written about the roles American reporters have played, often unwittingly, as messengers, recruiters and sources of information and disinformation since the 1940s. In a 1977 article published by Rolling Stone, Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter Carl Bernstein wrote a groundbreaking piece titled “The CIA and the Media.” In it, he wrote that journalists with the New York Times, CBS and Time Inc. were among the most valuable to the U.S. intelligence organization.

“In the field, journalists were used to help recruit and handle foreigners as agents, to acquire and evaluate information, and to plant false information with officials of foreign governments,” Bernstein wrote. “Many signed secrecy agreements, pledging never to divulge anything about their dealings with the Agency; some signed employment contracts, some were assigned case officers and treated with unusual deference.”

What I was considering doing paled in comparison, but I nevertheless agonized over the decision. I discussed it with the one person in my life I knew I could trust, my wife, Jo Ann, who had spent 14 years working on the newsroom’s administrative side of the Detroit News. She understood my dilemma and said she’d support me whatever I decided. I knew I should discuss it with my editors at the Detroit Free Press – I could trust them as well – but I also had a pretty good idea what they would say: The only way I’d get to Helsinki was on an assignment for the newspaper, and there was no way it would pay to send me there for a story about two players who might not be in Detroit for many years, if ever.

But there was something about this offer, this opportunity, this mission, that I couldn’t shake. In retrospect, maybe part of me was still fighting the Cold War. I remembered meeting those great players with the Soviet National Team in Quebec City for “Rendez-vous 87” – the two-game all-star series with NHL...